What shapes willingness to pay (WTP)?

By Steven Forth

Willingness to pay (WTP) is one of the most popular, and abused, terms in pricing work. Some people assume it equates to value. It does not. It is not even notionally a proxy for value and if your consultant or software vendor suggests that it is, then run the other direction. Other's believe it is fixed, determined by market forces. It is not. Willingness to pay is malleable and part of the work of a pricing strategy is to shape and indeed increase willingness to pay.

So what is willingness to pay? When is it useful? How can it be measured? How can it be shaped? These are critical questions for any pricing program.

What is willingness to pay?

In standard economics term, willingness to pay is paired with a willingness to accept.

"Willingness to accept (WTA) is the minimum amount of money that а person is willing to accept to abandon a good or to put up with something negative, such as pollution. It is equivalent to the minimum monetary amount required for sale of a good or acquisition of something undesirable to be accepted by an individual. Conversely, willingness to pay (WTP) is the maximum amount an individual is willing to sacrifice to procure a good or avoid something undesirable. The price of any goods transaction will thus be any point between a buyer's willingness to pay and a seller's willingness to accept. The net difference between WTP and WTA is the social surplus created by the trading of goods."

As the seller, you have a price you are willing to pay. The buyer has a price they are willing to accept. If WTA is lower than WTP then a deal can be made. The goal of the buyer is to get the price as close as possible to the WTA and the goal of the seller is to get the price up close to WTP. Or is it?

The problem with this framing is that it assumes WTP is fixed and knowable. It is neither. Again, WTP is highly malleable and context dependent. It changes depending on the competitive alternatives, the economic and emotional value, and how well that value is communicated. It is also subject to the uncertainty principle, measuring it changes it, and how you try to measure it matters.

When is Willingness to Pay useful (or not useful)?

There are times when you want an indication of WTP. This is mostly true in the negotiation phase. During negotiations the seller is trying to get the price as close as possible to the buyer's WTP while the buyer is trying to get the price down to the seller's willingness to accept. Giving the negotiator, who is often a sales person, some indication of what the willingness to pay might be can be very powerful, especially as salespeople are generally poorly equipped to negotiate when compared to procurement and supply chain managers. The best of the pricing software platforms try to do this. They infer WTP from historical transaction data and provide this to the sales as guidance. This is better than no guidance, but not as powerful as tools that can move WTP higher.

WTP is much less useful in another common application, setting prices for segments or packages. Some people attempt to segment markets by WTP, dividing all of the prospects into cluster by WTP. There are several problems with this approach.

It does not give any insight into what determines WTP. Two prospects may have the same WTP for very different reasons. If you don't know what is driving WTP you cannot design the most compelling package or value messages.

It does not help you to connect price to value. The central idea of value-based pricing is that the value metric (the unit of consumption by which a buyer gets value) should connect to the pricing metric (the unit in which you price). Different pricing metrics can lead to very different ranges for WTP.

Most measures of WTP are static estimates. In fact, WTP is dynamic and is changing all the time based on perceived alternatives, the flux of emotions in the buying process (customer journey maps can give insight into this) and perceptions of value.

All in all, WTP is a reductive number of limited use.

How can Willingness to Pay be measured?

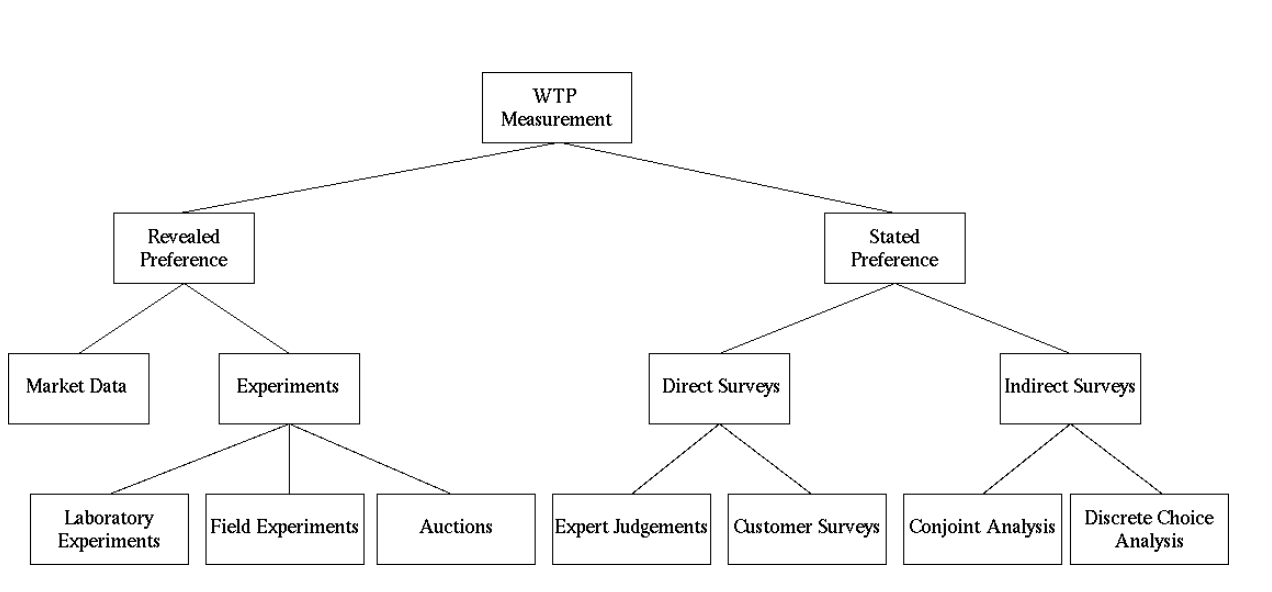

Traditionally there are two basic ways to estimate WTP. Christopher Briedert, Michael Hahsler and Thomas Reutterer have a good overview of this in their paper A Review of Methods for Measuring Willingness to Pay in Innovative Marketing, 2006. There are methods that look at actual transactions or experiments to reveal the preference, and there are market studies that are used to get a stated preference. The big pricing software platforms take the former approach, inferring WTP from variations in the prices actually paid by similar buyers. Market research firms tend to take the latter approach, using techniques such as conjoint analysis and discrete choice analysis.

Both approaches suffer from the limitation that they are trying to measure willingness to pay directly rather than get at the factors that actually determine the buyer's decision. A more powerful approach is to do what is called a Fermi decomposition (after the Nobel Prize winning physicist Enrico Fermi, in which one estimates a value or range of values by considering the inputs that determine the value. In the case of willingness to pay, these are the economic and emotional value drivers that we are familiar with from value-based pricing.

Product management guru Alan Albert made an important point in his interview with us.

"To date most of this work has been focused on backward-looking data, and the emphasis has been on understanding past customer actions in an effort to help guide future decisions.

In the future, understanding of customers’ perception of value will become more widely recognized as a more effective predictor of their future behavior. We will apply data science not only to behavioral data, but also to information about customers’ values. The integrated customer-centric analysis of these two types of data will fuel great advancements in pricing and product management decision-making." (From Product management and pricing skills - an interview with Alan Albert).

It is best to understand the inputs that drive WTP rather than trying to infer it directly. By doing so you will get insights into how you can shape it.

How to shape Willingness to Pay

The most important thing to understand about WTP is that it can be shaped, and it is the job of pricing to shape this useful symptom of pricing power. You should not try to treat symptoms of course. What matters is to understand what is causing the symptom and then to address the underlying causes.

In this case, what determines WTP are the same factors that shape pricing power. Your economic differentiation determines the range of prices that you could charge, the emotional value drives up WTP and your pricing strategy helps you decide the price you actually should charge.

We have covered a lot of ground in this post, so to summarize, Willingness to Pay is

A dynamic range, not a static number.

A symptom and not something that can or should be treated directly

Best investigated indirectly, using a value-based pricing framework that includes the content, economic value and emotional value

Something that can be shaped through customer targeting, value communication and having the right pricing metric

So by all means, try to track WTP. But do not confuse this with an actual value-based pricing strategy and limit your use of this metric to an indicator that can help sales in negotiations. Do not try to build a pricing strategy on Willingness to Pay.