Push Me Pull You - Your pricing is a system

Note: The title and image for this article are based on Hugh Lofting's story "Doctor Dolittle Meets the Pushmi-Pullyu".

By Steven Forth

Pricing changes can be tricky because each price is part of a larger system. Changing a price in one place can cascade across the system causing all sorts of unexpected consequences. You cannot think of a price change as a simple change to a number. That number can connect to all sorts of other things.

The first place to look is at anchoring and framing effects. These are terms from behavioural economics, that part of economics that tries to take into account how people make decisions in the real world. An ‘anchor’ is a value that other values are compared to. Pricing design includes the design of what value will be perceived as an anchor value. This is done by how and when the price is presented during the customer journey and what alternative is presented. Think of your favourite restaurant. What prices are easiest to find? They are likely designed as the anchor prices. When changing a price, ask:

Is this an anchor price?

Will it still be an anchor price after the price change?

How will changing this price change the perception of other prices?

Framing is the larger context in which anchoring takes place. At its most basic it is the definition of the next best competitive alternative. One of our clients had long compared its platform to survey tools. This made it look expensive even for a subscription of under $2,000 per year. This was poor framing as the real competitive alternative was not a survey but expensive and expert consultants, who would choose $50,000 or so for an engagement. By reframing their market, and focussing on a narrow segment where they could outperform consultants (your market segmentation is a key part of your framing) they were able to raise their prices to almost $20,000, a 10X increase. Note that this reframing includes both a narrowing of their target market and a change in the competitive alternative. The result was faster revenue growth and much higher gross profit.

Many SaaS offers come with tiered pricing. We see these on most pricing pages. There is entry pricing on the left, in between pricing in the middle and some form of enterprise pricing on the right. These tiered models are generally kept to a maximum of five tiers. These models have both anchoring and framing effects taking place. One thing we do at Ibbaka when assessing these pricing models is to see if the pricing is linear (on the left below), concave (middle) or convex (right).

In most cases, the linear models suggest that the person setting the price was running on autopilot. Concave pricing is designed (or has evolved) for markets where the lower end of the market is largest or is being targeted. The high price on the right makes the middle price look attractive. Convex pricing is used by companies that want to draw in customers and then upsell them. It works best when the upper end of the market has the most opportunity or is being targeted.

Many large companies are selling multiple solutions. In this case, the system dynamics go beyond the pricing of an individual offer to the role an offer plays in the portfolio. We have been writing about this in our series on Pricing your solution portfolio.

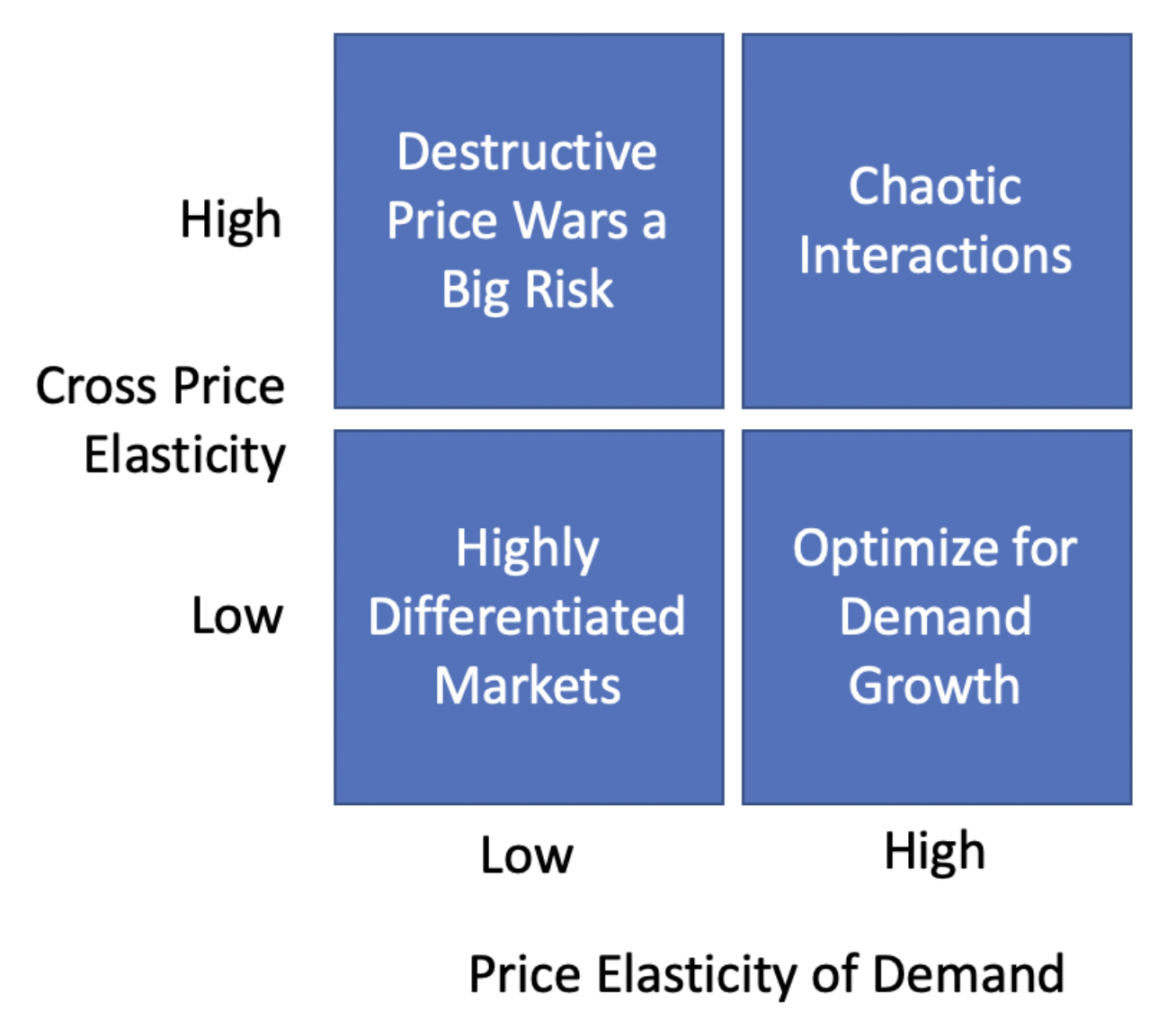

Of course, your pricing is part of an even larger system. The marketplace. Some of the most interesting system behaviours here are caused by the interactions between price elasticity of demand (how much aggregate demand is impacted by changes in price) and cross price elasticity (how changes in price lead people to switch from one vendor to another). We have written about these interactions in several places, most recently in How to hire a pricing consultant.

There are three levels at which pricing acts as a system.

Within the solution,

This is where pricing is part of the anchoring and framing and plays a big role in how price and value play out across the customer journey.

As part of a portfolio

This is where the offer has a role to play in the overall portfolio and is at a certain point in the technology adoption cycle. (Not all offers are necessarily in the same part of the cycle, some may be targeting early adopters, others may be in rapid growth mode, while others are approaching obsolescence.)

In the market

This is where pricing and packaging moves by competitors’ impact on your own pricing strategy (Michael Porter’s Five Forces model is a good way to think about what the alternatives are).

Given these complex interactions, pricing needs to be treated as a complex adaptive system. Most people lack experience designing and managing such systems, and as a result, they either fall into analysis paralysis, or fail to take pricing actions as often as they should as it gives them a headache to think about it.

Pricing actions are some of the most powerful things you can do to improve your business, so ignoring pricing, pricing by throwing stuff at the wall, or pricing based on what competitors do are all recipes for poor performance. In early stage innovation, they can even kill the new product or service.

What to do?

Here are a few simple questions to get you started on assessing your pricing actions

Is the current price acting as an anchor?

Will it still be an anchor after the price change?

How will the anchoring change?

How is pricing currently framed?

Will the framing be changed by the price change?

Do you need to change the framing?

How is pricing framed by your brand?

Will the price change reinforce the brand or undermine it?

How is your tiering system designed?

What role does each tier play? Is it playing that role effectively?

Is your tiered pricing linear, concave or convex? Why?

How will the pricing change impact framing and anchoring within the tiers?

What role does the offer (and its pricing) play in the portfolio?

Consider anchoring and framing effects across the portfolio

Is the role of the offer in the portfolio changing? (Has it moved along the technology adoption cycle?)

How will the price change impact market dynamics?

Which of the four quadrants are you operating in?

How will your competitors respond?

How will your customers respond? (But remember, you can afford to lose some volume as part of a price change, especially when the result is a higher gross margin or lifetime value of a customer.)

Are new alternatives emerging that will reframe your offer and its pricing?

Use the Five Forces model to see where alternatives may emerge.

Clayton Christensen’s disruptive innovation model may provide additional insights.

The three different layers do interact, and this can lead to some unexpected outcomes when you change prices. But don’t let this get in the way of acting. The only way to really understand a complex adaptive system is so observe it as it responds to change. So make changes, observe the outcomes and course correct. Pricing is a dynamic discipline.

Note: The title and image for this article are based on Hugh Lofting's story "Doctor Dolittle Meets the Pushmi-Pullyu".