Listening for what is not said – skills of top consultants

Last week, we asked some of the world’s top consultants “What are the skills of a top management consultant?” One of the most intriguing comments came from Duncan Sinclair of Deloitte Canada, who noted the importance of:

“Being able to hear what is left unsaid.”

I have several conversations over the past week on what this means. It seems that different people interpret this quite differently.

One innovation consultant, who also has training in the police work, assumed that this is primarily about detecting when people are willfully concealing something. There is a hidden agenda for the consulting work, one that is not being shared with the consultant.

Another person I discussed this with spends most of her time coaching leaders at large (very large) companies. She took a more psychological approach, and heard this as a comment about people, even top executives, not wanting to admit certain things about their own motivations, or perhaps, not even being aware of what their own motivations are.

I have also been doing some work with a very capable and experienced marketing consultant, Kirk Hamilton. Kirk has given TeamFit advice and he is one of the key investors at E-Fund, leading due diligence teams and advising the fund’s investees. He has pointed out that one of the most important things for companies to do is to

“Understand the key assumption they have made and test to see if it is true.”

This is almost as interesting as ‘listening to what is not being said,” and it is just as hard. The problem with assumptions is that we are often not aware we have made them. Uncovering assumptions is a critical part of a consultant’s job.

(Addition: Kirk reached out to me after reading this to point out that it is Roger Martin who encourages consultants to ask the question “What would have to be true for our strategy to succeed?” See “Five reframing questions every strategy leader should ask” by Alex Lowy.)

The key themes

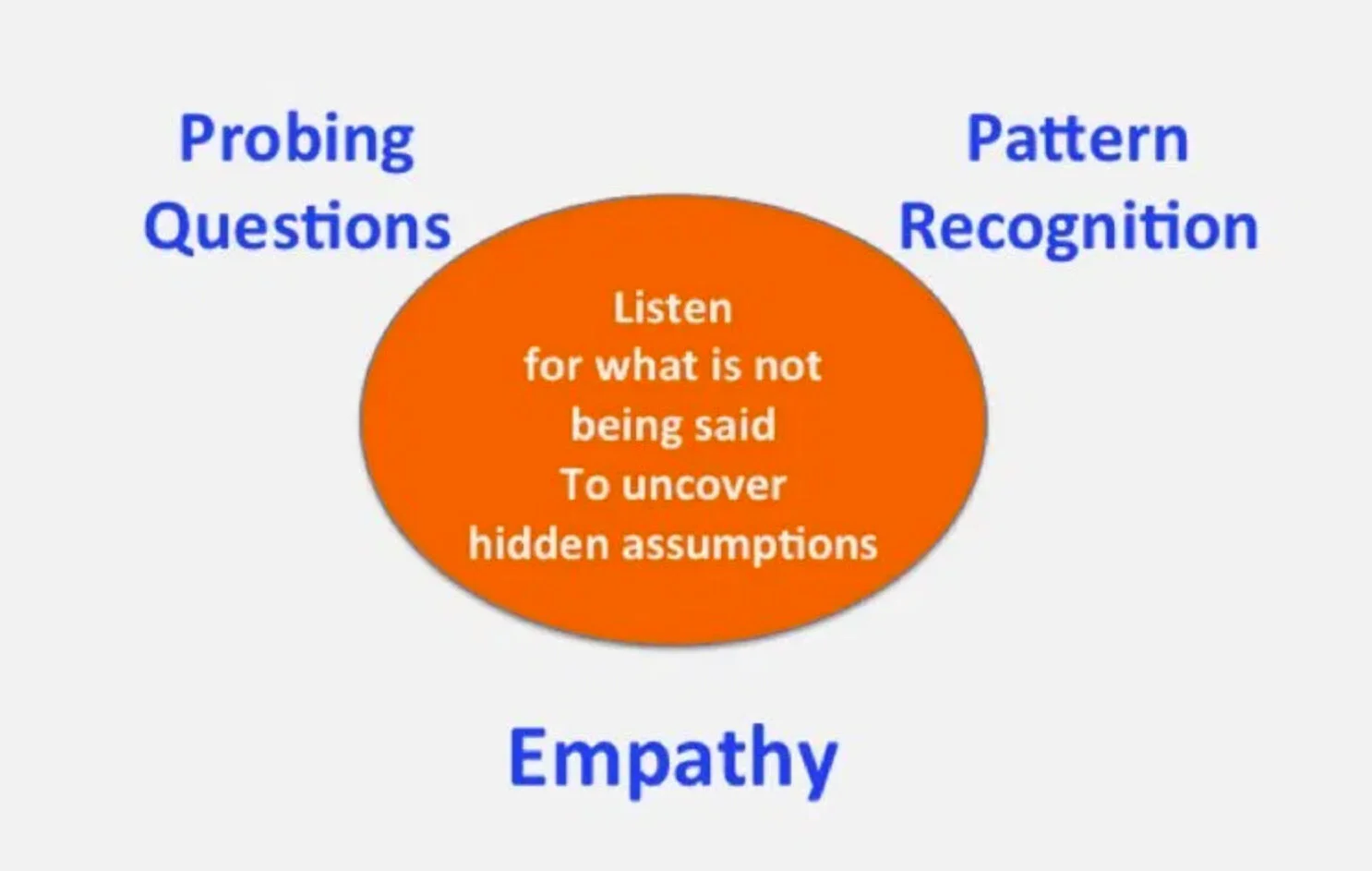

So how do we get good at “hearing what is not being said” and “uncovering hidden assumptions”?

Probing questions

It helps to have a good set of probing questions handy. Most consultants build these over time. They are specific to the problem area the consultant works in. A pricing expert will have a different set than someone engaged in organizational design.

At TeamFit we are developing a set of questions around skills. One use of our platform is in skill audits. A skill audit discovers the skills of an organization and probes for skill gaps and skill risks that will prevent an organization from achieving its goals.

We have learned not to start with skills. Instead we ask people about their daily routine, who they work with, and their own goals. Once we have established a context with the person, we lead them to talking about skills. We are especially interested in the skills that they use with other people (we are trying to tease out the pattern of complementary skills at the company) and the skills used to achieve goals. Putting skills in the context of goals is a first step to uncovering skill gaps.

Another tactic is to ask people to identify the component skills that contribute to any important skill. We look for very abstract or general skills; things like ‘critical thinking’ or ‘software development’ and ask what skills contribute to the more general skill. It is important to ask this of multiple people as each person will have a different set of component skills. Understanding these different internal skill models reveals a great deal about how the company is connected and where there are disconnects.

Pattern recognition

The other key to hearing what is not being said and to uncovering assumptions is pattern recognition. Experienced consultants are good at recognizing patterns. A number of skills contribute to pattern recognition – the ability to see part-whole relationships, the ability to trace connections, multithreaded causal analysis – but perhaps the most important are

(i) experience of at least two business cycles and

(ii) experience in at least two different industries.

To get good at pattern recognition one should study patterns in all their wonderful variety. Architects and software designers are way ahead of business people on this, so learning key patterns from these disciplines has a lot of transfer to business. The people best at pattern recognition generally are very curious and have open minds.

Here is a nice short piece on “How to develop pattern recognition skills.”

Empathy

Catching what is not being said requires emotional intelligence. A purely rational approach will miss critical cues. You have to be able to put yourself in your client’s shoes. And not just their shoes, but those of their clients, and competitors, and stakeholders, and …

Empathy is the best way to get an idea of what is not being said, and what might prevent it from being said. Is the omission

An oversight, something that has been lost sight of

A taboo, “we don’t ask about that”

A deception, a sin of omission

Repressed, “that is too hard to admit or think about”

Makes the consultant sound a bit like a therapist (and some of the best consultants to consultants, like Chris Argyris or David Kantor functioned like therapists).

Can you develop empathy as a skill? I am not sure. The experts think it is something established in early childhood and is based on trust. As a consultant, do you trust your clients? Not a naïve trust. You still need to probe and uncover those hidden assumptions. But without trust you will not have empathy and you will not be able to create those lasting relationships that create value for both sides.

Is empathy one of the skills you have on your TeamFit profile? It is not on mine, and I am wondering what my teammates will say when I claim it!