Strategic Choice: LinkedIn opts for a closed garden

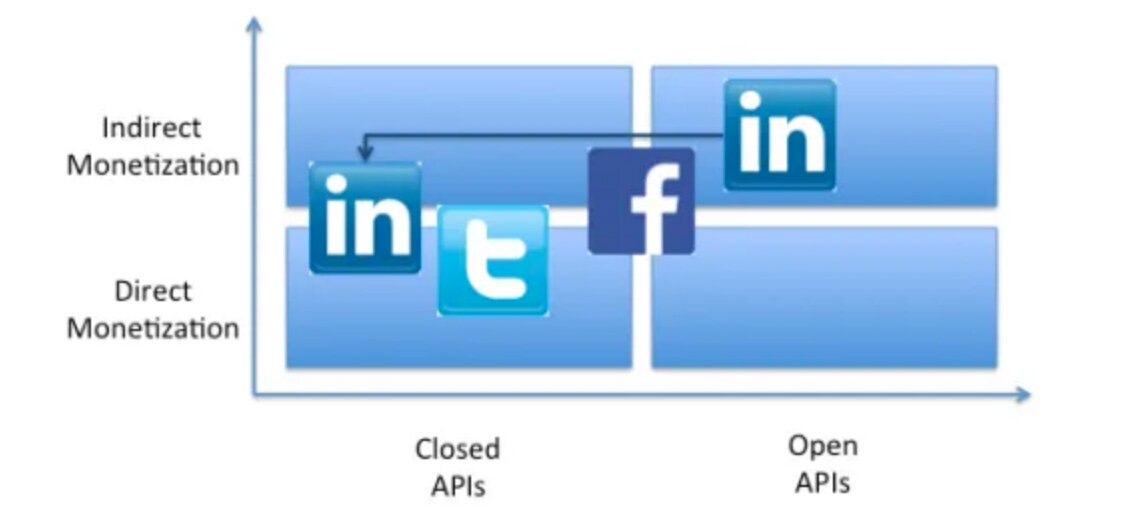

LinkedIn executed on an important strategic decision this month (May 2015). As it had announced well in advance (no one can claim they were taken by surprise by this), it closed off access to its platform to all but a small set of carefully selected partners.

Basically, LinkedIn’s leadership decided to limit access to companies that support its business model but do not compete with it. Then, within this limited group of potential partners, it has become very selective about whom to work with.

LinkedIn explains its current policy on a nicely design website called LinkedIn Partnership programs. In the language system of Daniel Jacobsen (who led a similar change at NetFlix), LinkedIn has decided to move from a Large Set of Unknown Developers (LSUD) to a Small Set of Known Developers (SSKD).

This is a real strategic choice for LinkedIn. As Roger Martin points out in his Harvard Business Review article, the first question to ask of any strategy is if the opposite strategy is also viable. The strategic choice available to LinkedIn was to build an open ecosystem for a large set of unknown developers or a closed ecosystem for a small set of known developers. It chose the latter.

LinkedIn is not the only social network to choose the closed strategy. Twitter did so back in 2012 (Ben Thompson has a good review on his Stratechery blog). Facebook has a more open approach at present and there is an open question around Google – what will it do with Google+ and how will it leverage its detailed information on people to shape social networks, especially professional social networks.

The reasons for LinkedIn’s choice are pretty clear:

There have been problems with companies using the LinkedIn API to spam users or to gather information about people and companies that the companies did not intend to share or have aggregated.

LinkedIn does not want to create an asset that other companies use to compete with it – it does not want to create and support the companies that may disrupt it.

These are compelling reasons – protect ones users and defend one’s strategic position. So why do I think the open strategy is also compelling?

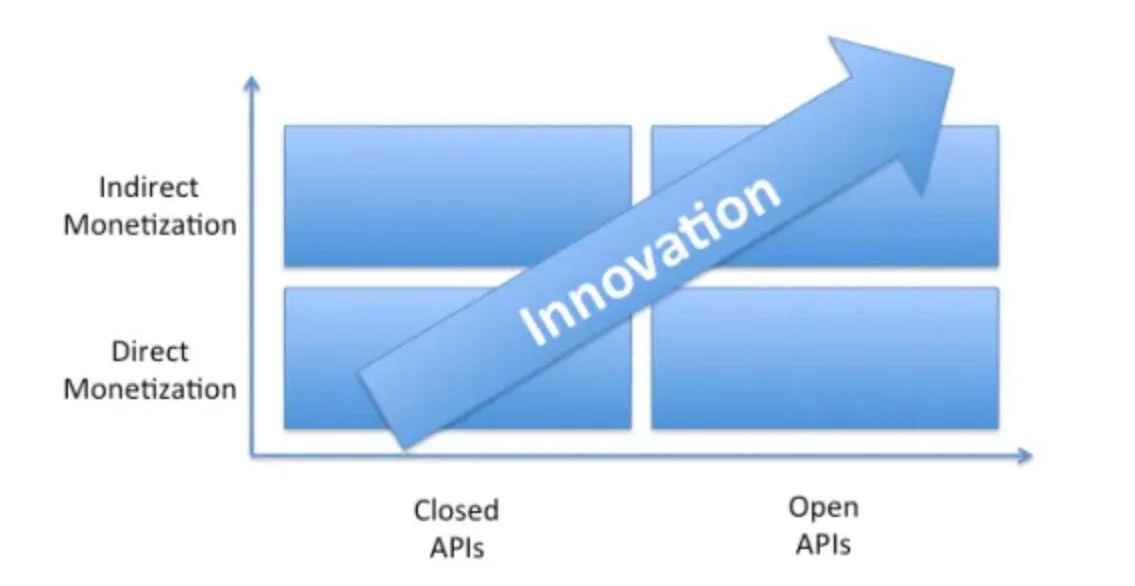

From a business perspective, there are two main reasons: innovation and data ownership.

The closed strategy where one works with a small number of known partners shuts down innovation. We live in a world where continuous innovation is a critical source of value creation, see Steve Denning’s work on this. The thing about innovation is that it comes from surprising places and it is usually most active at the edges, where systems rub up against each other. In other words, a lot of innovation happens when APIs get connected. And this is unpredictable. By moving to a closed approach LinkedIn will, over the long-term, reduce the innovation in its ecosystem.

It will also reduce the amount of data that can flow into its ‘economic graph’ (integrations flow both ways). In the words of LinkedIn CEO Jeff Weiner, from way back in December 2012:

“Our ultimate dream is to develop the world’s first economic graph. In other words, we want to digitally map the global economy, identifying the connections between people, jobs, skills, companies, and professional knowledge — and spot in real-time the trends pointing to economic opportunities. It’s a big vision, but we believe we’re in a unique position to make it happen.”

My gut feel is that by choosing to close in its ecosystem LinkedIn has kneecapped its ability to build the economic graph and to find the disruptive partners that will help it create value. We just don’t know how that value will be created or what information is needed in the graph.

A more serious question about the closed strategy turns on data ownership. There was a sharp backlash against LinkedIn’s decision from the open data community. The concern is that LinkedIn is claiming a level of control over people’s data that it should not have. “Data about me should belong to me and I should be able to do with it as I like. And LinkedIn should only be able to use my data in ways I agree to.” There is even a website encouraging people to Stop Using LinkedIn. It starts by helping you download your data, then close your account, and proposes many alternative sites for different types of users.

But therein lies the problem. The Stop Using LinkedIn site lists dozens of alternatives for different job roles: for start-ups, developers, designers, marketers, data scientists, etc. Good to have all these alternatives. But I generally need to build connections across different roles in order to build a team, and having all these different data sources is a challenge.

It will be interesting to see how LinkedIn manages these challenges. Will it be able to keep up in a world of open innovation? And how will it manage the thorny issues of shared data ownership? The vision of a global economic graph is compelling. But can it be delivered inside a walled garden?

A note on the image: this graph gives a global view of the evolution and diversity of metazoan neuropeptide signaling . Two points: evolution leads to diverse connections between wildly varying forms; communication (data integration) is at the heart of evolution.