The Keys to Adaptation are Humility, Curiosity, Experimentation - An Interview with Olivier Aries

Steven Forth is co-founder and managing partner at Ibbaka. See his skill profile here.

The emerging profession of skill and competency management draws on several different roots. Learning and instructional design is one source of inspiration. Many people in the profession got their start as learning designers or curriculum developers, and in the standards area many of the people who led the creation of learning standards are now working on standards for skills and competencies (see Competency Model Definitions - The IEEE Ups Its Game). Another source of inspiration is the decades of work done on performance improvement, inspired by Thomas F. Gilbert’s work, see Human Competence: Engineering Worthy Performance. There is a third strand here, one that is as important as learning and performance, that is knowledge management.

Knowledge management is a bit out of fashion these days, but it may be poised to make a comeback, informed by new technologies and a growing recognition of the importance of sharing and mingling ideas.

Olivier Aries is one person with a deep understanding of these trends. While at the global consulting firm A.T. Kearney, he led Fortune 100 transformation projects before going on to become the head of knowledge management. He has also managed professional services for The Predictive Index and is now putting together The Thrive Collective.

We spoke with Olivier in this strange pandemic year to get his insights into how he has developed his own skills and how he sees the future of work.

Ibbaka: Ibbaka talent is fairly obsessed with skills and skill development and how they enable people to reach their potential. How have you developed your own skills over your career, to bring you where you are now?

Olivier: I think the main model has been observation and apprenticeship. Except for formal education, including and up to my MBA, I don’t remember having been formally trained in anything. I do remember though, sometimes feeling as though I’ve been thrown in the deep end and learning under the fire by just observing and repeating what people around me, presumably more senior, were doing.

Behaviorally, I have long been what the Predictive Index categorizes as an Adapter, meaning that I’m very tuned to what’s happening around me and I flex more easily than most to new circumstances. When it comes to upskilling, that’s an asset for me. It’s easy for me to observe and pick up things, and frankly, I’m glad this is the case because I don’t remember going through a lot of formal training. I’ve spent most of my career in consulting and consulting is in many ways a school of apprenticeship. One gets thrown onto projects, if you’re a junior, you get input from your manager, you sit with them in the meetings, you understand and capture what seems to be working. Sometimes they coach you formally, but that’s not that frequent. So, I would say apprenticeship has been my primary mode of upskilling and learning.

Ibbaka: What is necessary in order to be an effective apprentice? What kinds of people learn through apprenticeship and what was it about you that made this a good mode to learn? Or was it the best mode for you to learn?

Olivier: Consulting has really shaped my way of thinking. Consulting forces you to be flexible and adapt to a variety of industries and projects. In my case, there are a couple of things I’ve found to be effective when you’re in that environment.

The first is to be humble – humility. It’s acknowledging that when you start you have less knowledge than you should have. In fact, that’s nearly the definition of an entrepreneur, an entrepreneur is somebody who has a vision that is beyond the accessibility of resources. As an apprentice, you need to understand you have needs that are beyond your current expertise. Recognizing that gap and being humble about it, is the starting point.

The second is curiosity, openness, the desire to learn. By definition, in an apprenticeship model, the learning is on you. It is what you decide to make of it because there is not that much kinetic energy around you to force you to learn. You have to have the drive and the curiosity.

Number three is that you need to have a certain willingness to experiment, because by definition you are learning on the spot and learning as you are doing. Every action has a certain amount of risk, that you don’t have in a formal training model where you first learn and then you apply. In an apprenticeship model, you apply as you learn, so you are bound to make mistakes and have to accept them.

Humility, curiosity, and a certain risk-appetite are the three ingredients needed.

Ibbaka: How are you preparing yourself and your colleagues for the future of work?

Olivier: I don’t know what the future of work will be. I have some ideas about what it might be, but maybe I’m overly shaped by what’s happening. I think uncertainty is the future of work.

There’s so many factors that will influence what’s happening, society is changing, so is technology, as are the demands of work itself. The bottom line is, I don’t really know and the only thing I can do is apply the apprenticeship model, which is to observe what’s going on and try to make sense of it.

It’s sort of naïve to say that these days you have to be adaptable, but today adaptability goes beyond the tactical, say working from home, to the strategic. Strategic adaptability is what we need.

As you know, my career itself, in many ways has been adaptive. I wanted to do consulting, I went into consulting, but after that it went in unexpected directions. I think we have to make peace with that approach. We don’t really know where things are going to go, the only thing we can do is to be curious and understand what is going on and try to do our own scenario planning. Again, back to the apprenticeship model, acknowledge that whatever the future is, it's unlikely to come neatly packaged.

It’s going to be messy. We are going to have to experiment and be willing to go where the learning is. I hate to not be more specific. I am trying to read articles, trying to talk to friends, trying to make sense of it all, and try to see what it means for me. Where are the opportunities? What are the risks? The things that I should prepare myself for.

Ibbaka: Olivier, you’ve mentioned sense-making a few times, and making sense of things. What does sense-making mean? What is the ‘sense’ in sense-making?

Olivier: When I’m consulting with clients I always say that people fundamentally need two things. They need meaning in their life, understanding why things happen and in particular why things happen to them. The second thing they need is control. They need to have a sense that they can direct things and that they have agency.

I think to be successful in anything, you need to have options. To have options you need to anticipate things, therefore, you have to understand the flow of things. You need to be able to somehow predict.

This could be as simple as predicting the jobs that are going to emerge in an industry and how you will fit in. Are you poised to grow, get promoted, or as you are sensing that you’re out of sync with the organization, in which case, maybe it's time to reconsider what you’re doing, what your job is, your skill-set, what you want to do. For me, meaning is this, it is trying to see the trends and the flow in daily life so you can start to make predictions and generate options.

Ibbaka: We were talking about the future, what do you see as some of the different possible scenarios for the future of work?

Olivier: What we are seeing this year, what we’ve seen in other parts of society, is this increasingly fragmented world of work. The world is increasingly split into at least two broad classes of haves and have nots.

The haves are people like you and I – we are knowledge workers, we have networks, flexibility, working from home, some of us play mini-golf in the yard. I go kayaking and bike riding every morning. In many ways, I’ve gained more in the crisis than I’ve lost.

On the other end of the spectrum, you have employees and workers who have no flexibility, no power, who are physically bound to their job, generally at low pay.

The gap between these two groups is increasing. It's reflective of that gap we’re seeing in society in general, and around wealth. The second home market in the U.S. and, in particular, the North-East here, has been exploding. You can’t buy a boat anymore, all of them have been purchased. At the same time there are forty million people out of work, and just in Virginia, I know there have been 50,000 evictions. This is insane. That gap is insane. We’re seeing that same gap in work. So, when we say, “future of work”, we should say “future of works”, because I think its going to increasingly get segmented between knowledge workers, white-collar jobs, and other categories that are “in control”.

The other types of work lack control and people are struggling to find the meaning in what they do. They are literally being buffeted by what is happening. So that’s one way of seeing what the future could look like.

Another trend is the increasingly transactional nature of work. We have seen this play out during the crisis, where going virtual is the norm for those of us who are lucky to have the flexibility. You see that we are starting to lose the fabric of what makes a team, what makes relationships, because the interaction is sort of disembodied. It becomes more transactional and task focused. In many ways, they’re just a new form of the gig economy where people go where the need is, and they become disconnected from any sort of work network.

One way of looking at the future of work, is this increasing transactionional idea of work itself. You’re going to be like a free agent, within your own company, or across companies, going where you find the highest value and best work-life balance. On the other side, you’ll have people working in meat-packing plants, who have none of this. They are cogs in a machine. They are not free agents, they are transactional agents with no control.

Another way of looking at this is looking at the bigger society and seeing two trends. One, I think towards greater individuality in everything. When you think of all of the networks in life – church, family, the town, the neighborhood, all of these are frayed. There are multiple indicators of that increased individuality in life in general, people are just maximizing their own value without much attention paid to the network. If that applies in work as well, what’s left of that big network which used to be the company, the organization, this feeling of being part of a team? If this is fraying too, then we are going towards a free agent model of work.

Now, we are also starting to see a counterweight against this. Social justice, the environment, all those considerations are fundamentally community-based. It’s people saying that you can’t just maximize your individual value, you have to think about the value to the community. If this applies to work at some point and we see the same reaction, it may rebalance towards greater integration, greater focus on the employee as a person, greater focus on job satisfaction, maybe a longer-term view on skills and fulfillment. Companies are maximizing quarter-to-quarter results. For employees that’s the same, as you’re trying to maximize the fit with the job in the short-term – is this guy doing the best he can do for this position right now? There is virtually no focus anymore on, “Where do I want this person to be in ten years?”

And so, maybe under the pressure of society being forced to think about bigger issues that have longer time frames, work will also see this shift and people will start to be more inclusive at work, pay more attention to development and fulfillment.

A couple of years ago, Michael Porter, launched an initiative at Harvard on American competitiveness. This was an attempt to shed light on this idea that companies are increasingly maximizing their own value at the expense of the community and the expense of their employees, and therefore, ultimately at the expense of their own market - literally shooting themselves in the foot. Porter has this idea that for American Capitalism to survive, it has to refocus on the community. The focus has shifted to how companies and capitalism can be an agent of change. This could be a counterweight to the trend towards individualization of work, the transactional idea of work, the gig economy. So, who knows, there are glimmers of hope, but I see us living in an increasingly polarized world.

Ibbaka: You have a great deal of experience with change management. You’ve led change management programs and you’ve coached organizations on change management. What role will change management play in helping individuals and organizations prepare for the future of work?

Olivier: I think you can see that two different ways. One is that change management can be seen as a sort of a tactical tool. That’s the way most large consulting firms are using it. We have this big change, this big initiative, that ultimately might bring more value to the organization, sometimes at the expense of employees, maybe sometimes to their benefit. These tactical change management programs are more about ‘how do we make people accept the change.’

I think true change management would take a longer view, maybe a more integrative view, and say, “How do we change things so that people really do benefit from change?” Change management can be an amazing tool for thinking more broadly about how to try to maximize value for all. I’m not really aware of many organizations using change in that latter model, but again, someone like Michael Porter would say it's actually all about change. It's how you take control of change for the benefit of all parties. Michael Porter has recently said that you have to try to affect change at the society level by pressuring companies to improve workers conditions, because that’s the only meaningful change left.

Ibbaka: In this time of pandemic, what have you been reading to ground you, to stimulate your thinking and your own ability to think about change?

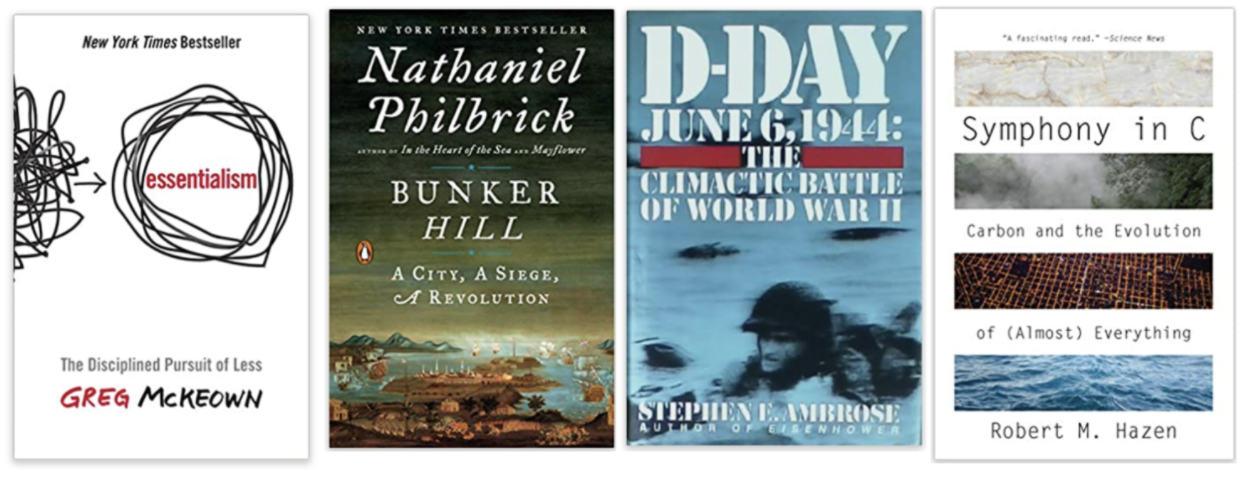

Olivier: You might be surprised! Four books. Number one is “Essentialism: The Disciplined Pursuit of Less” by Greg McKeown. Why? Because in the midst of all the uncertainty, he says that “the main thing is to keep the main thing, the main thing”. Number two is “Bunker Hill: A City, A Siege, A Revolution” by Nathaniel Philbrick. How the American Revolution became the American Revolution without anybody wanting this to be an American Revolution. How crowds, lack of communication, and messiness can create a groundswell support for things that you may or may not control. The best example of how not to do change management! On the opposite side of this spectrum, I’m fascinated by this book “D-Day: June 6, 1944: The Climactic Battle of World War II” by Stephen E. Ambrose. Which is the opposite - How do you keep control? Essentially, it is change management on a massive scale in a highly complex environment with a high level of unpredictability. By many measures, D-Day was the most complex human endeavour in history, just by the sheer complexity of it. It’s been a constant fascination for me. I’ve also been reading a book (“Symphony in C: Carbon and the Evolution of (Almost) Everything” by Robert M. Hazen) about the cycle of carbon, because it’s a reminder in many ways that we don’t really control what’s going on. Think of the macro scale of things happening to us as individuals and society. So it’s a bit of a reminder that we try to control things, but the reality is we have very little influence and we have to accept it.

Ibbaka: How do you see the different systems in the talent management ecology evolving?

Olivier: To be honest, I don’t have that good of a grasp on the different solutions. What I can tell you is that there is a sort of paradox to these solutions in general. I think we’re seeing a greater focus on the employee as a person. Maybe I have a biased view because I’ve spent the past couple of years around behavioural analytics. But you’re working on skills, and that’s the same thing. There’s been a groundswell of interest in work-life balance, fulfillment and mindfulness. Maybe we are trying to get back to the Constitution: work also needs to be about “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.” It’s kind of messy, and it’s bumping up against all of the other things we’ve talked about, the transactional nature of work. But one can feel this desire people have to go back to something more fundamental. The question is the way to get there. The tools are actually owned by companies and organizations. Predictive Index is a tool for individual development that is purchased by the organization. There is a contradiction there. The organization, despite what they are going to say, is going to be very tactical, practical and have a bottom-line focus on employees. They just want them to be as productive as possible. If the way to get there is to make them happy and fulfilled, then great. There could be other ways. The paradox I see is when will employees take control of their own development and fulfillment? Because right now, the tools are owned by a corporation so there is a bit of a conflict of interest.

When I was at PI (The Predictive Index), there was this discussion for a while on whether and how to give control to the individual? This is hard because the individual is not paying. We asked ourselves if we should offer a consumer tool, so people would have their own toolkit that they could take to different organizations where they work throughout their career. Right now, those tools reproduce the relation of power between the organization and the employee. Companies decide who gets access to the tool, who uses it, who has the license, who becomes a user. There is a fundamental flaw here.

Ibbaka: I want to probe on this a little bit. Can you say more what approaches were considered? What other approaches did you consider in order to give the individuals more of what you call “meaning and agency”?

Olivier: Let’s follow an employee, we will call her Sarah. Sarah is going to go into an organization that uses DiSC or the Predictive Index or similar tools. Through her organization, Sarah may be exposed to these tools and thereby gain greater self-awareness. She becomes more effective in that environment, understanding her colleagues better, she’s more effective on teams. Then Sarah decides to move to a different organization. When she leaves all those tools and knowledge are left behind. Not quite, maybe the behavioural profile she has is still hers, she might have a copy of it somewhere, but when she goes to a different organization that doesn’t have these analytics at her disposal and she is left blind and deaf. She doesn’t know who she is dealing with and she doesn’t understand the team dynamics. That’s just crazy. Sarah wants to continue to be effective and productive. Suddenly she is bereft of the tools that she used to have. At some point, the thought on our product development team was, “should we try to create a different version of the tool that becomes widely accessible publicly, that could even be free for people, through LinkedIn or Google”? We would make it sort of our gift to the world. People would then use the tool for themselves and with those around them. Now they would be in control and have the resources they need to self-develop. The world around them would also have meaning because analytics would explain and predict why people act a certain way. We didn’t pursue this for many reasons but I strongly believe the opportunity is still there.

Ibbaka: Ibbaka has two design rules that are relevant to this.

One is people should own the data that has been collected about them. So that when you leave a company, your skill profile should travel with you. That doesn’t prevent the organization from owning it as well. It’s not like a cup, it’s digital so that two people can own it at the same time. Ownership rights can be different for the organization and the individual. The data should travel with the individual over the course of their life.

The other, somewhat related, design rule is that an individual should be able to determine what goes on their profile. So, if I suggest a skill to you, you should be able to decide whether or not to accept that skill. Individuals should have control over assessments. Estimates of expertise are generated algorithmically and created in many different ways. But people should be able to decide whether to expose those assessments or not. Those are two design rules that we have. Do you have any thoughts or comments on those?

We say more about this in our post Ownership of data in a collaborative age: Three unworkable approaches and a way forward

Olivier: That is exactly what I was talking about. One, because I think it makes sense if we have a true, genuine interest in upskilling people and making them better free agents, wherever they are. But frankly, I think it's also good marketing. As people move around and you want them to be agents of change and say hey, I have this skill profile, it’s amazing, now you know me, and I want to know you. How do you know how to work together most effectively if we don’t have these insights about each other? So, I think it is smart on many levels.

Ibbaka: How is your community, however you choose to define that, adapting to the pandemic?

Olivier: On the surface, what we’ve done is try to close ranks a bit. I think there’s been more communication, maybe trying to be a bit more authentic. In moments of crisis, it's hard to keep your feelings to yourself and not enquire about people who do not seem to be riding the wave that well.

I think it’s a natural human reaction to seek the support of the group. What I think is great, it has created a bit more curiosity to open up more to others. If anything, this crisis has made people realize that many things we take for granted, well we shouldn’t. One of the things we take for granted is accessibility to friends, family, and colleagues. We sort of take for granted that everything was great on Monday, so that everything will be great on Tuesday. Well, no – whether it’s from a health standpoint, a work standpoint, a travel standpoint, many things that seem obvious are not. So, I think that forced people to be more curious and open up more to people, because we realize all of this is very fragile. People, organizations, and communities can disappear easily. So, I hope we can experience that additional human warmth and curiosity.