The jobs of talent scenarios

Steven Forth is co-founder and managing partner at Ibbaka. See his skill profile here.

The future is not settled. We have all had that lesson reinforced over the past few months (I am writing in mid May 2020). It is especially important for leaders in HR and talent management to take this to heart as we are responsible for preparing the workforce for the future. But what future scenarios are they planning for? There is a lot of uncertainty as to what future will emerge post Covid 19 and what demands that will place on us.

Please take our survey on Mobilizing Talent After Disruption

One of the most powerful ways to prepare for the future is through scenario planning.

Skill and competency models can play an important role in any scenario planning process. These models can act as an input into the scenarios and they can be used to test how well prepared we are for the different cases. Once we know how well we are prepared we can look for ways to build resilience and adaptation.

Ibbaka combines an outward looking market focus with an inward looking talent focus. It is only by connecting these that one can really discover and then execute on strategy. You can read about applications of scenario planning to pricing here.

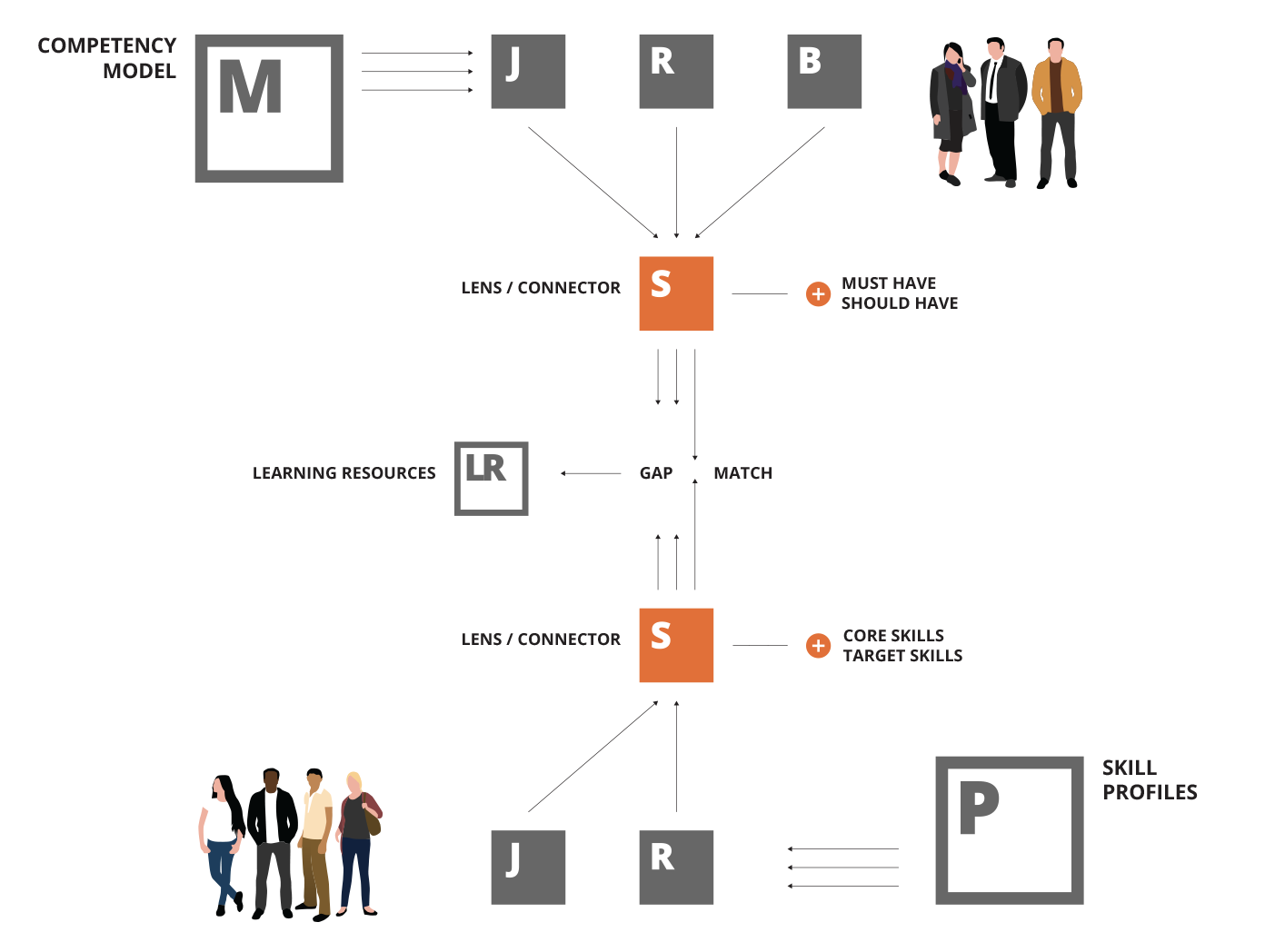

Before we dig in, it is worth clarifying what we mean by a ‘skill and competency model.’ It is more than a list of skills or a skill library. A good competency model connects Jobs and Roles to Responsibilities, Tasks, Behaviors and the Skills that support these. Some models extend to include values; others are linked to learning resources and performance support. A robust model goes beyond the individual to support teams and team building and energizes potential. Learn more about the design of competency models.

What is scenario planning?

Scenario planning is a planning framework to help us understand that that more than one future is possible. It was developed in the 1960s by RAND Corporation and made famous during the first oil crisis in 1973 by Shell Oil. Shell had used scenario planning to anticipate the possibility of a supply squeeze and price spike. When it saw this happening it already had plans for how to respond. Shell has an active scenario planning program to this day. The next generation scenarios are due to be published in June 2020 (I imagine these are being revised). Learn about the history or scenario planning at Shell and see many examples.

At its simplest, scenario planning generates four future scenarios by combining two critical uncertainties. A critical uncertainty is one that matters to your business or to the lives of your workforce. How do you identify a critical uncertainty?

There is a significant probability that the scenario will occur (usually at least 10%, so scenario planning does not protect you from true Black Swan events)

You will adopt a different strategy for each scenario (there are meaningful choices to make)

The scenarios tell different stories about the future and how you will respond or shape it

Below are two highly simplified scenario sets. In the purple scenario set the HR and talent management team is planning for two growth scenarios and wants to understand what skills will be needed for a growth strategy that is focused on internal growth vs. one that relies on leveraging gig workers. The skills needed for these four scenarios and the appropriate management metrics will be quite different.

In the green scenario set, the HR and talent management team has a critical uncertainty around the future business model and a choice to make on whether to focus on resilience or adaptation (we will write about the tension between resilience and adaptation later this month). Each scenario will require a different skill and competency plan. We look at three different uses of competency models in scenario planning below.

You may be thinking ‘this is too simple, the future does not resolve into four distinct scenarios.’ Too true. Scenario planning is a way to simplify our thinking about the future so that we are prepared to take action. It helps us realize the possibility of and then to plan for different alternatives. There are some applications of scenario planning where six or nine scenarios are used (one can have three different states for one or both critical uncertainties). Advanced users have experimented with using three or more axes of critical uncertainty. Cisco did this back in 2010 when it was working with GBN (now part of Deloitte) to develop scenarios for the future of the Internet in 2025. A Powerpoint summary of this work can be found here. But in most cases, a simple 2x2 matrix of four scenarios is the best place to start. It is easy for people to understand and remember.

A simple process for scenario planning in talent management

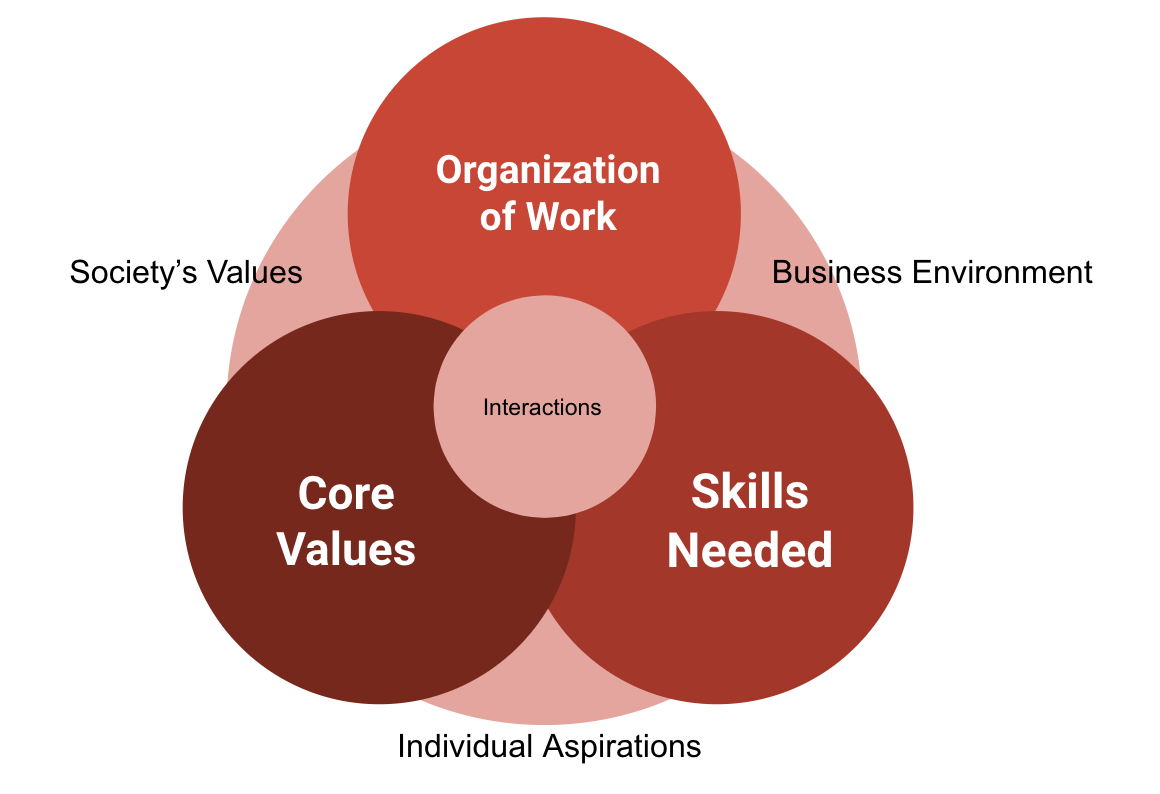

Talent management scenarios tend to be organized around three dimensions.

Organization of work

Critical skills required

Core values

These interact in many different ways. In some scenario planning work you will pick two uncertainties from the same dimension. Do this when you need to go deep into possible futures for one specific area. In other cases, one wants to explore the interactions and picks a critical uncertainty from two of the three dimensions. When you do this, the details of each scenario are often framed in terms of the third.

Talent management operates in the context of the wider environment. The business environment, society’s values and individual aspirations all shape how we work, and there can be critical uncertainties in these areas as well. Speculation that different generations have their own aspirations for work has been used in some scenario planning projects to explore how these will impact organization design.

The process is as follows:

Identify trends about which there is already meaningful certainty

Examples are demographic trends, demand trends, sustaining innovations, events that we know will occur but are unsure when they will occur (like pandemics).

Identify critical uncertainties

A critical uncertainty is where more than one future could emerge. These uncertainties are critical because they will lead to different actions and outcomes that have important consequences. In most cases limit this to two or three possible outcomes. Even if there is a continuum of outcomes or more than three outcomes it is easier for humans to manage a limited set of scenarios. Trying to account for all possible scenarios can lead to 'analysis paralysis.'

Combine two critical uncertainties

This is a powerful exercise. Pick several different different critical uncertainties and try combining them in different ways. Look the the patterns that emerge. Which generate different futures that will require different actions.

Select the critical uncertainties and construct four scenarios (or nine if you are using three critical uncertainties or three states per uncertainty)

As discussed above, the common practice is to limit oneself to two critical uncertainties and four scenarios. All for scenarios should be seen as possible. It is not necessary that all be desirable or that one be the most desirable. In some advanced applications it is helpful to use multiple states for each critical uncertainty or to use more than two critical uncertainties, but this leads to complexity that can actually make it more difficult to understand and prepare for scenarios.

Name each scenario

Give each scenario a name so that it becomes memorable and you can refer to it easily.

Analyze the implications of each scenario

Investigate questions such as

- Who is impacted

- How long will the impact last

- How will the impact change beliefs about the world

- How will the impact change behaviors

- How will the impact change decision making

For talent scenarios, consider the impact on

- Organization of Work, Skills Needed, Core Values

- Adaptation or Resilience or Efficiency

- Foundational Skills or Applied SkillsCreate stories about each scenario

Turn each scenario into a story about that future. Stories are one of the most powerful ways to promote understanding and memory. A scenario is not complete without a story.

Identify early indicators for each scenario

Ask what the early indicators are for each critical uncertainty, what will suggest how each uncertainty will resolve. Do this first for each critical uncertainty used for your scenarios and then for each scenario.

Decide on actions for each scenario

What are the critical actions you will take under each scenario? It is often useful to divide these into three time frames: at the beginning of the scenario, in the midst of the scenario, at the end of the scenario.

Apply best practices for decision making and make it clear what will trigger the action, what resources are needed to execute the action, what information is needed to execute the action, what outcomes are expected.Establish a review mechanism

Periodically (usually quarterly or annually) review the other critical uncertainties that you identified in Step 2. See if any of the critical uncertainties have resolved so that there is no longer uncertainty. When you do this you may identify new critical uncertainties. Decide if you need to refresh your scenarios.

Three ways to use scenario planning in talent management

The core idea here is to have a competency model for each scenario. In some cases the model will include a change in how work is organized. For example, many companies are trying to become more adaptive and to promote internal mobility (the ability for people to move from job to job or role to role inside the company) by moving from a Job Focus to a Role Focus (see The Future of Work is a career braid of our different roles). The shift from job focus to role focus generally requires a different competency model with more roles and with skills associated with the ability to switch roles or to take on multiple roles.

Prepare for rapid action

This is how Shell used scenario planning in response to the 1973 Oil Shock. It had a plan developed that it could execute on if a scenario was realized. Competency models that support a change in scale (rapid growth or the need to reduce the workforce) are an example of this. Developing the option to deliver a new service is another example.

Build resilience or adaptation or efficiency

Recent experience has reinforced the need for resilient organizations. A resilient organization is one that can take an external shock and return to stability. A classic use of scenario planning is to build an organization that is resilient under different scenarios. A related approach is to build an organization that can adapt to different scenarios. In some cities major infrastructure investments need to be viable across more than one scenario. See Scenario Planning for Cities and Regions Managing and Envisioning Uncertain Futures by Robert Goodspeed. The same approach can be applied to talent management. After establishing your scenarios, ask the following:

What skills are common across all scenarios?

What skills are unique to each scenario?

What foundational skills will build resilience?

What foundational skills are needed for adaptation?

What organizational model works best for each scenario (is there a model that works across scenarios)?

Shape the future

The most powerful use of scenario planning is not to respond to the future, nor to build in resilience and adaptation, but to shape the desired future. The classic example of this is the Mont Fleur scenarios that were developed in South Africa at the end of apartheid. Different groups of stakeholders, some of whom had been violently (literally) opposed to each other came together to find a path to a better future, and to avoid the worst outcomes.

Can you do this for talent management at your organization? Before you start with this, it can be useful to do this as an individual. What future scenario are you working towards? What are the critical uncertainties that could lead you off on a different course? Over the next few weeks, we will share some personal scenarios for our own futures.

Once a few of the talent leaders have done this, ask what kind of company maximizes the probability that my organization will enable my own aspirations. It is hard to lead a company into a future that you do not want to be part of.