How does your firm manage allocations?

It is human nature to assume that the way we are used to doing things is the normal way to do them. As most of us have worked at only a few different professional services companies, we assume that the way in which we have seen people get assigned to teams is the standard way. But as we’ve talked with more and more people about team allocation, we have discovered a lot of variety here.

A lot.

Just who are the allocators?

Over the past few months Ibbaka Talent has spoken with people from many different companies about how they go about assigning people from their pool talent onto teams. We have done this through open-ended conversations, but we asked the following questions:

Who is responsible for allocating people to teams?

How wide do you cast the net when looking for team members?

What do you consider when making allocation decisions?

After speaking with many companies of varying sizes and business models, we have started to see some interesting patterns emerge. We found that companies seem to differ along four key dimensions when it comes to team building.

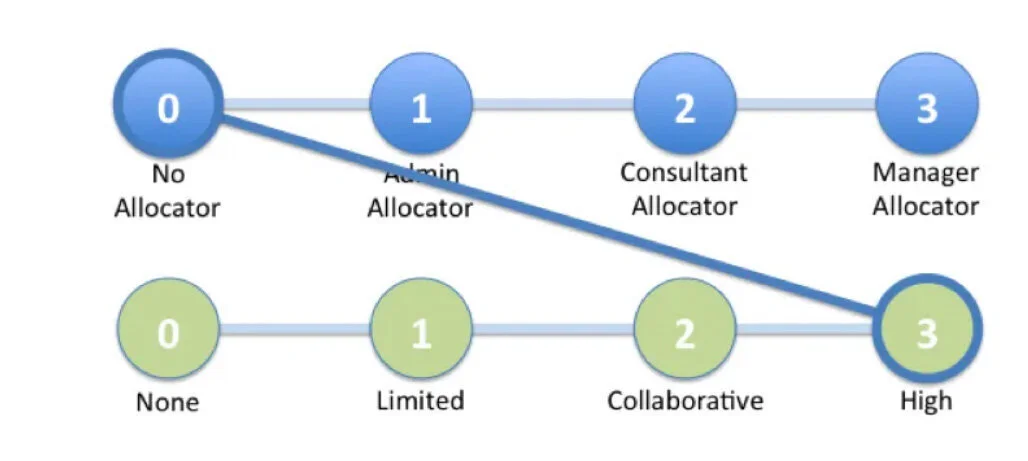

One of the key questions is “Who are the allocators?” Allocators are also known as resource managers, team builders, internal HR experts, or simply as that “person who knows everything about everybody.” But not every company uses allocators, in some cases, consultants are expected to get themselves on teams while partners fight over access to the best people. This paradigm is sometimes described as “survival of the fittest” or “the free market at work.”

Can consultants decide what they work on?

Allocators allocate consultants, so the next question is how much control over projects/team do consultants really have (autonomy)? In some companies consultants basically do what they are asked. “You…we need a pharma pricing analyst in Berlin on Monday, pack your bags.” In other companies, consultants have a big say in what projects they go on and can turn down work (of course they still need to keep their utilization ratios high so there is a built-in tension there).

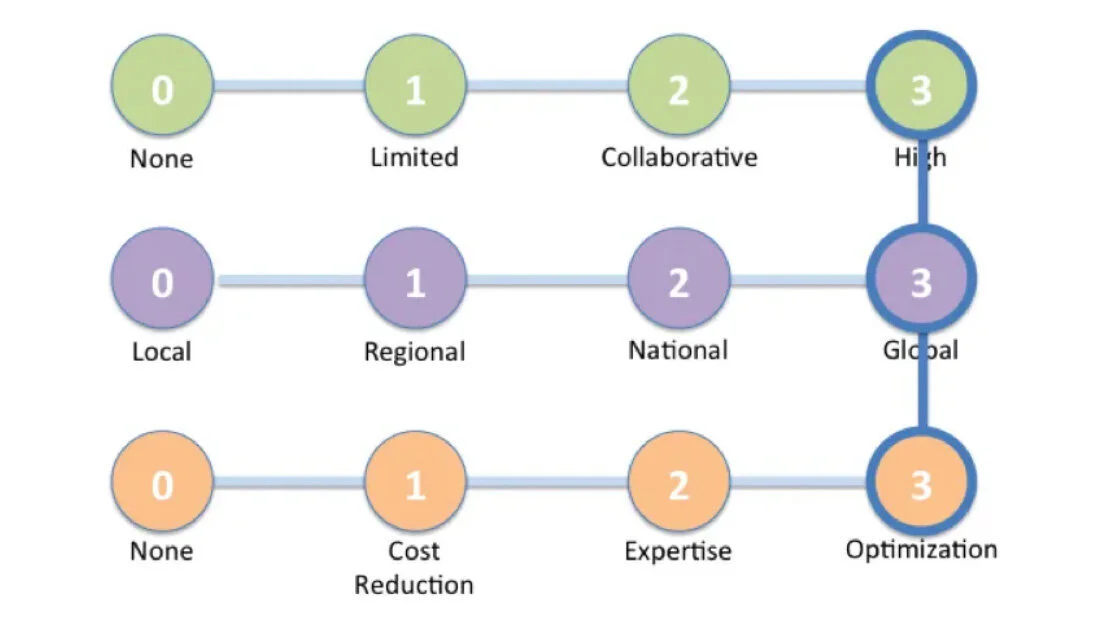

There are some companies that try to keep teams local and staff projects with people from the same office. “If it is sold in Portland it will be staffed in Portland.” Other companies have regional or national allocations, and a few just pick the best people for the team regardless of where they happen to be. Our initial data suggests that companies using global allocation strategies tend to be either very large or very specialized.

Bringing in people from outside

The fourth dimension we have identified is the use of external consultants. There are four common approaches: avoid using external consultants; use external consultants for low value, rote tasks to lower costs; use external consultants for expertise that the firm does not have internally; use the best person for the job regardless of whether they are in the company or not. We call the last of these “optimizers.” They follow what The Economist calls “The Hollywood Model.”

Quick question: Take a few minutes and think about the companies you know. Where do they fall on these four dimensions? (And if you could send me an e-mail to share your own experiences.)

More than four dimensions to assembling teams

There are some other dimensions that we think may help to differentiate approaches to team building and resource allocation.

The importance of utilization and optimizing utilization rates

The degree to which consultants have fungible skills (one person can easily be replaced by another, either at the beginning of a project or even mid project)

Contract structure – fixed price vs. time and materials vs. outcomes

Does that cover the range? What other dimensions should we be considering? Let us know in the comments below…

Patterns emerge for forming teams

Now that we are looking at companies through our four dimensions of team allocation, we are beginning to see three main patterns: consultants with low autonomy managed by senior people, consultants with high autonomy and no central allocator, and companies with global teams who use external resources extensively.

In companies where consultants have very little autonomy, allocations tend to be managed by more senior people who get people on projects where the project need their skills:

In contrast, in companies where consultants have complete autonomy (which seems to be rare) there tends to be no allocator, and the partner who sold the project or the project manager who will lead the delivery does allocations.

A third pattern we are seeing— and one that is quite common—is where there is extensive use of external, independent consultants.

An external consultant is generally autonomous; responsible for their own career and finding projects to get on; and are generally willing to work with distributed teams. We found a pattern of autonomous consultants working on distributed (even global) teams with companies that focus on team optimization. We believe that teams who leverage both external consultants and distributed teams try to find the absolute best people for any given team—regardless of where that person my physically reside.

Just the tip of the iceberg

These are very preliminary results, and no doubt we will discover more patterns and have to replace one or more of our four dimensions—or even add whole new dimensions to the model. However after speaking to tens of consultants and allocators over the past several months, we feel this is a solid first step to understanding this complex topic.

The best practices for managing allocation, and the systems needed to support it, will depend on the approach a company takes to allocating people to teams. TeamFit is committed to understanding these differences and supporting best practices.